| Location | St Kilda, Victoria, Australia |

| Date | 2002 |

| End User | General public, Needle Exchange, The Prostitute Collective, Salvation Army |

| Client | Needle Exchange, The City of Port Phillip, The Melbourne Festival |

| Designer | SueAnne Ware |

| Research Assistants | Adrian Drew, Yvette Romanin |

| Installation | Blake Farmar-Bowers, Matt York, Harley Blacklaw |

| Funding | The Melbourne Festival |

| Cost | $30 000 (Australian)/$32 988 USD |

| Area | 10 km/6.3 mi |

Red poppies commemorate heroin deaths. Photo: SueAnne Ware

Most memorials stand tall to commemorate fallen heroes and past events, but in 2002, in Melbourne, Australia, the Anti-Memorial to Heroin Overdose Victims occupied the streets and sidewalks of the St Kilda neighborhood, its tough aesthetic illustrating the hard-scrabble existence of the people it remembered.

The anti-memorials lined the streets the Esplanade for 10 km (6.3 mi). Image: SueAnne Ware

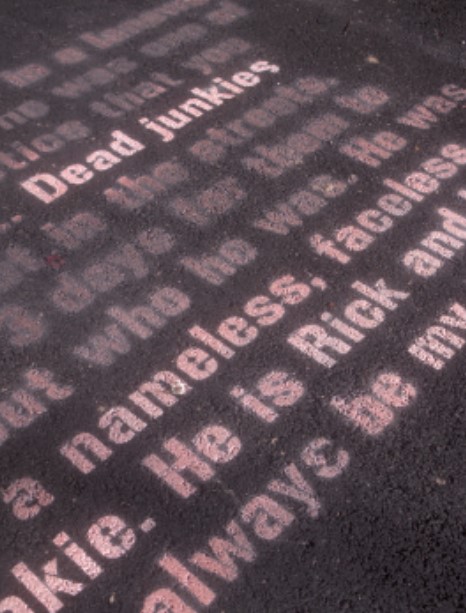

The installation was designed by SueAnne Ware, a professor of landscape architecture at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. She and her collaborators filled planters with red poppies. They stenciled spray-painted quotes from drug users and mourning family members on the sidewalks, and attached resin memory plaques to the flower boxes with the cherished objects of overdose victims. The installation linked three streets in the St Kilda neighborhood to confront distinct social groups and classes: the drug users and outreach organizations of Grey Street; consumers and business people on the Fitzroy Street commercial district; and families and tourists strolling the Lower Esplanade along the beach.

“What we see in the public realm is art that you can’t touch,” Ware says. “We wanted a sense of vulnerability; we placed the plaques low to the ground so people had to bend down and really engage with it.”

Eventually people started walking over it, which is what we wanted. We never intended to create a cemetery in the middle of the sidewalk.

—SueAnne Ware, landscape architect

Several groups contested the installation, though the fact that it was temporary tempered some of their concerns, Ware says. The Returned and Service League, a veterans organization, was offended by the use of red poppies, which has become a symbol of Remembrance Day, commemorating the British Commonwealth dead from WWI. The pharmacists of Fitzroy Street, many of whom did participate in clean needle exchange programs, did not want the area to become more known for drugs.

top left image: Closeup of stenciled text. Photo: SueAnne Ware

top right image: Closeup of Resin Memorial Plaque that holds momentos of the deceased. Photo: SueAnne Ware

bottom image: A pedestrian crouches to inspect one of the flower box memorial plaques. Photo: SueAnne Ware

Public reaction to the memorial was mixed. “One client [of a treatment center] came up to me while we were putting in the installation, and he said, ‘We don’t need art, we need rehab,” Ware remembers. Someone even scrolled “Wish you were heroin” next to the installation in chalk.

During the first week the anti-memorial also had an unintended effect on pedestrians. “People treated the text as if it were a grave; they wouldn’t walk on top of it,” Ware says. “Eventually people started walking over it, which is what we wanted. We never intended to create a cemetery in the middle of the sidewalk.”

Other members of the community were grateful for the memorial, and were especially appreciative of the tone. It redefined those who had died as people instead of anonymous statistics. “People left flowers and wrote us e-mails thanking us for remembering those that they loved and missed,” Ware recalls. “Many of the family members and other IV drug users were incredibly grateful to see their loved ones recognized with dignity and not shame.”

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT