| Location | Port-au-Prince; Leogane; Papette, Haiti |

| Date | 2010 |

| End User | 1.1 million internally displaced refugees following the January 2010 earthquake |

| Project Partner | Habitat for Humanity |

| Design Agency | Architecture for Humanity |

| Design Team | Heidi Arnold, Eric Cesal, Adam Saltzman, Schendy Kernizan, Cara Speziale |

| Funder | Individual donations |

| Unit Cost | $700-$6000 USD |

| Recommended Upgrades | $675-$1620 USD/unit |

| Web Resource | http://openarchitecturenetwork.org/projects/transitional_to_what |

An aerial view of the damage in Port-au-Prince, Haiti after the January 12, 2010 earthquake. Photo: International Organization for Migration

Temporary or transitional shelters were deployed en masse to Haiti following the magnitude 7.0 earthquake that rattled Port-au-Prince on January 12, 2010. Designs varied from ad hoc wood and plastic sheeting construction to sturdier structures secured with hurricane ties (metal straps that reinforce structural connections) and built on foundation piers. Costs ranged between $700 and $6000. With hurricane season looming, many non-governmental organizations were concerned about the safety of families living in flimsy shelters and called on Architecture for Humanity for help.

Plastic buckets full of cement support a temporary structure. Photo: Adam Saltzman/Architecture for Humanity

People displaced by natural disasters will often live in transition for several years succeeding the event in structures intended to be temporary. This indefinite time frame in Haiti was due to the large number of people displaced by the earthquake and the unclear land tenure archive, according to Eric Cesal, regional program manager for Architecture for Humanity.

To assist relief organizations building temporary structures, Cesal and a team of architects evaluated the most common structures in Haiti and provided a report with recommendations on how to make them last longer and withstand the fast-approaching hurricane season.

The effort resulted in the Transitional-to-Permanent Housing Evaluation Report, a 51-page document released in fall 2010 that examined and compared 10 emergency shelter types in common use throughout Haiti. The team assessed shelters built by various organizations including ADRA, Center for Haitian Studies, the International Organization for Migration, Habitat for Humanity, Samaritan’s Purse, the Spanish Red Cross and World Concern. The report evaluated the structures but also provided design solutions and outlined cost predictions and steps to improve safety or extend a given shelter’s lifespan.

The study proposes simple, low-cost modifications to transitional shelters—in many cases changes that promise to extend the lifespan by 2 to 3 years. One of the options is a priority upgrade package that includes a floor/foundation upgrade, and the addition of hurricane strapping and siding. A second tier of upgrades covers structural additions such as corrugated steel roofing, block foundations and cladding such as pressure-treated wood siding. Finally, the report recommends infrastructure and interior upgrades, adding a latrine, providing water collection, pouring a floor slab or adding interior finishes.

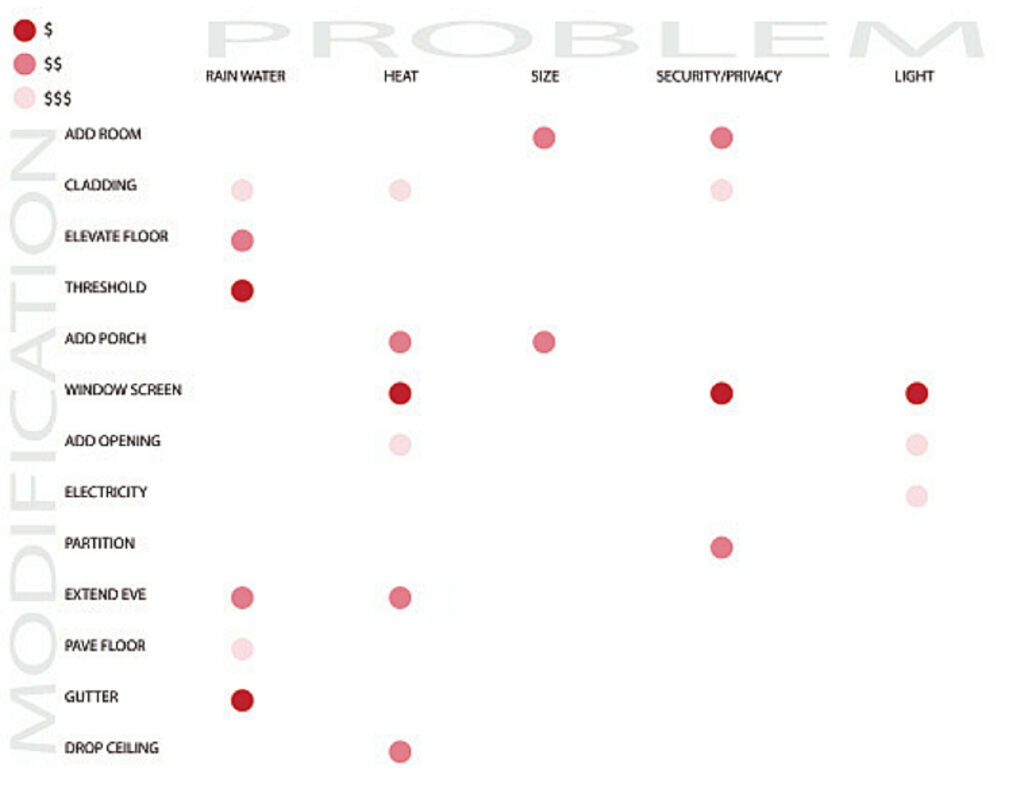

The proposed modifications were analyzed by how much they would cost and what problems they would fix. Image: Architecture for Humanity

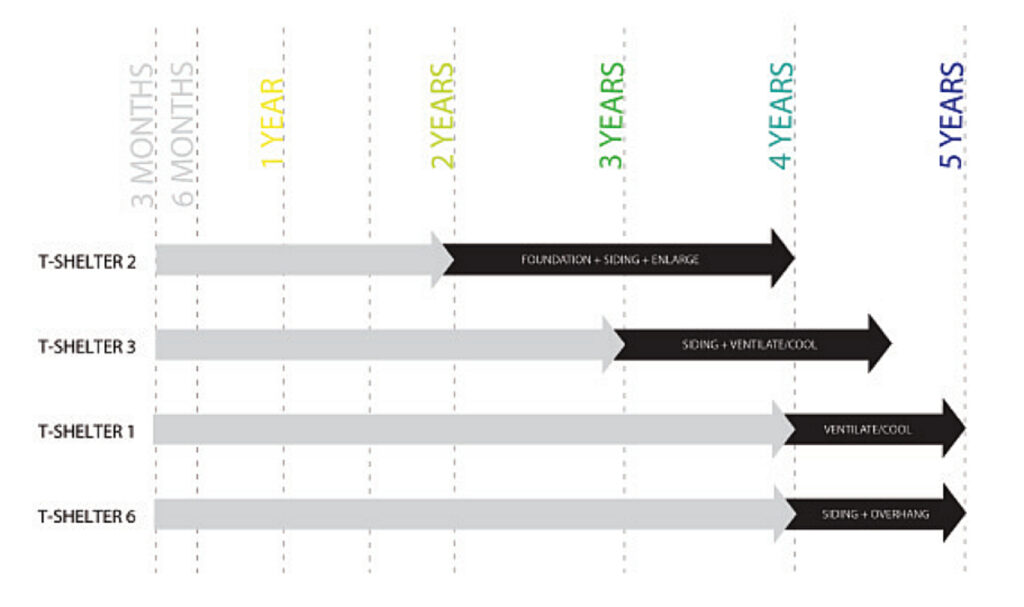

The proposed modifications aimed to extend the lifespan of transitional shelters. Image: Architecture for Humanity

“How can you make a better shelter and not increase the cost?” volunteer Heidi Arnold recalls wondering. “Some of them only cost $700 but some of them cost $3000 and were obviously a better shelter. Then again, some companies were making a better shelter just by using resources more appropriately, using local labor, saving on time.”

The team identified other areas for improvement. “A lot of the residents had really similar issues or problems that needed to be addressed,” Arnold says. “Ventilation was a major problem. [Residents] would have to close the shutters at night for security. So people would add ventilation high up on the walls where others could not break in as easily.” Although these ad hoc changes did not necessarily compromise the structural integrity of the shelters, their inhabitants often were compelled to add their own customizations. “Typically the shelters were really hot during the day, so a lot of people were building additional shade areas and outside kitchens,” Arnold recalls.

In the case of shelters made from plastic sheeting, many people would seek out scrap material as siding to provide a measure of security. Others cut out back doors themselves. “It’s really important to have an emergency exit in the back,” Arnold says. An additional door provides a critical second exit, particularly in light of the rise in crime following the earthquake.

The team was careful to prevent its findings in a constructive way. Although the report did not establish correlations or mention any shelter organization by name, the findings were shared with each of the organizations whose structures were evaluated. The report was also shared at the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Haiti Shelter Cluster, a panel of major organizations that met monthly during relief efforts.

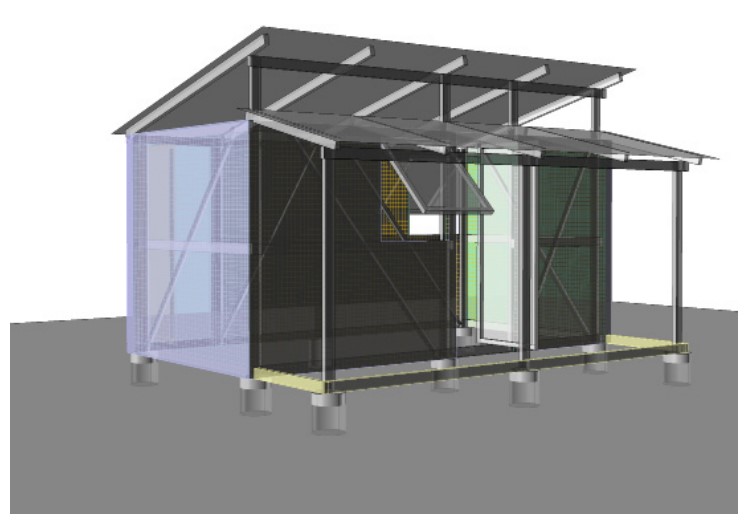

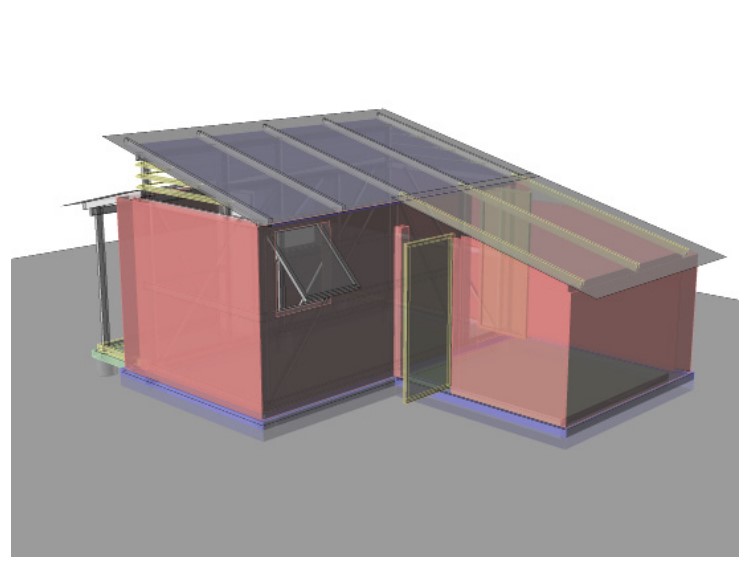

Many temporary shelters in Haiti would not withstand a hurricane without the modifications pictured. Image: Transitional to What?/Architecture for Humanity

Photos show different structural modifications suggested in the report. Image: Transitional to What?/Architecture for Humanity

CHF International, which was among the agencies whose shelters were evaluated, used the third-party findings to lobby for—and secure—a 15 percent increase in funding to make improvements to its existing shelter model. “[The study gave] us the clout to go back to our donors and say we really need to move away from the plastic sheeting, we need to focus more on hurricane straps as well as plywood, because of the security issue,” says Ann Lee, CHF International’s emergency program director. “And we actually used the study to go back to our donors and get funding for the remainder of our shelters. Out of 2000 shelters, we had between 500 and 1000 shelters left to construct, and we were able to change the plastic sheeting into plywood. It was great for us to be able to justify that.”

To ensure that the findings were made widely available, the report was published on the Open Architecture Network and the Inter-Agency Standing Committee websites and can be downloaded at no cost.

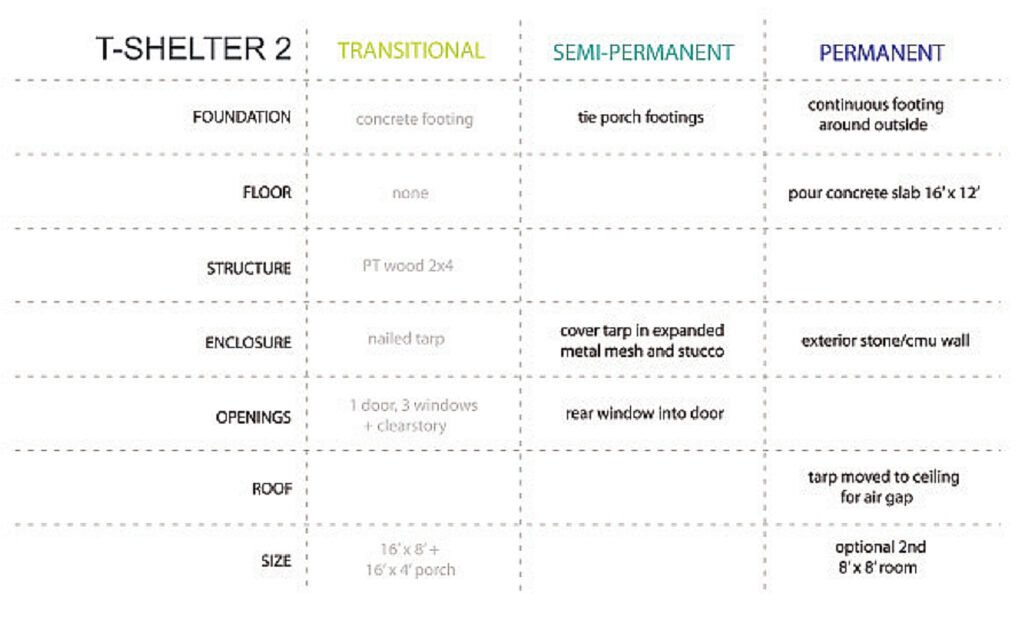

The study proposed specific modifications to each shelter to make it semi-permanent and permanent. Image: Transitional to What?/Architecture for Humanity

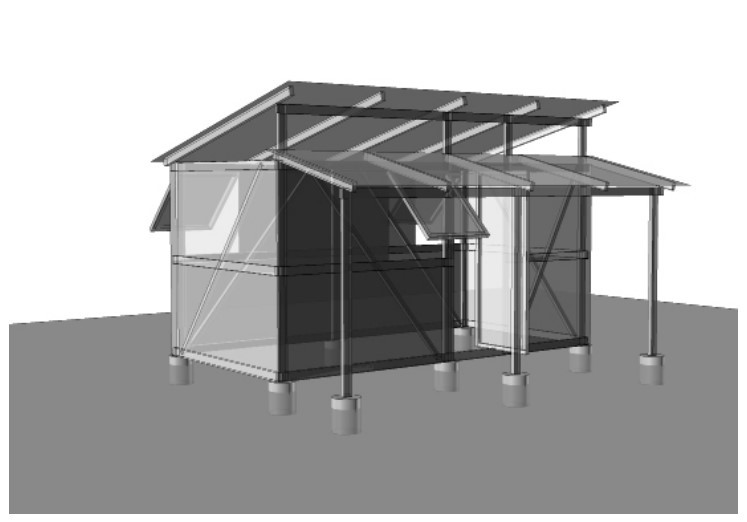

Renderings of T-Shelter 2 show the modifications from top left (existing shelter) to bottom right (permanent with added room). Image: Adam Saltzman/Architecture for Humanity

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT