| Location | New Delhi, India, and 30 other locations in rural India and Cambodia |

| Date | 1999–present |

| Sponsoring Organizations | NIIT Centre for Research in Cognitive Systems, Hole-in-the-Wall Education, Government of Delhi |

| Concept | Dr. Sugata Mitra |

| Design Team | Ravi Bisht, Ashoo Dubey, Sanjay Gupta, Vikram Kumar, Dinesh Mehta, Dr. Sugata Mitra, Nitin Sharma |

| Major Funding | NIIT, Government of Delhi, ICICI Bank, World Bank |

| Cost per unit | $10,000 (three-computer VSAT kiosk) |

| Area | 324 sq. ft./30 sq. m (per kiosk) |

Dr. Sugata Mitra’s Hole-in-the-Wall school program has become a portal to the future and a connection to the outside world for many Indian children.

Mitra, a professor and chief scientist at NIIT’s Centre for Research in Cognitive Systems, has been working to provide high-speed Internet access to children in rural areas of India since 1999 with rewarding, and often surprising, results.

The first computer terminal Mitra installed was in an abandoned, garbage-strewn lot near NIIT headquarters in New Delhi. He mounted the computer in a concrete wall and monitored the activity via video camera from his own computer. He discovered that most of the people using the computer were children between the ages of six and 12 who spoke little English. What they were learning astonished him. He then launched a campaign to install computer kiosks on school playgrounds, where children were encouraged to learn free from adults, exams, and all the other trappings of formal education.

Mitra says his original concept was based on the assumption that children could learn basic computer skills without instruction— an assumption that proved true. He reports that children learned to surf the Internet, download music, use a mouse, copy, drag, and save—all without direction. They also created their own computer terminology. When asked by a journalist, “How do you know so much about computers?” one child responded, “What’s a computer?”

Even more telling, Mitra and his team of researchers found that children were able to transgress communication barriers, abandoning their native language Web browser for the English version of Microsoft Explorer. In one case children created a drawing using a Microsoft Word template that Mitra himself didn’t know existed. By providing computers he found that children will work in groups to teach themselves basic skills and knowledge. However, Mitra is careful to point out that the kiosks are not intended to replace education but to give it a boost, freeing up scarce dollars for instructors to teach subjects children cannot learn on their own.

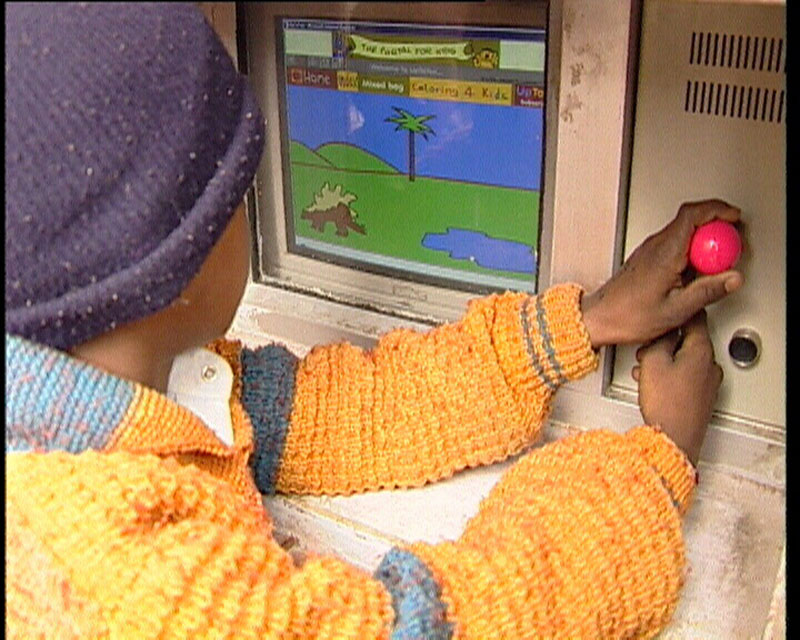

Children crowd around a kiosk in Vivekanand Basti, New Delhi, India. All photographs Hole-in-the-Wall Education

Since the introduction of the kiosks, parents have reported other interesting developments. They say their children have learned to share and work together, assigning time slots for terminal use without the aid of adult supervision. Often parents become the project’s most ardent advocates, in some cases paying the electric bill for the kiosks from their own earnings in order to keep the computers up and running. (To avoid these costs, some kiosks, such as the one in Stok, a village in the Ladakh district of northern India, are being run on solar power.)

The Hole-in-the-Wall schools do have potential drawbacks. Mitra fears children may become targets of Internet crime. There’s the task of monitoring who uses the computer and for what purposes. And there’s the problem of maintenance. Design plays a role in mitigating many of these issues. For example, to deter adults from monopolizing the computers, the kiosks are designed to be more physically comfortable for children. To cut down on maintenance, the computers have very few moving parts and only the most basic function keys. Sensors on the terminals detect the presence or absence of finger movement and help conserve power. Finally, to discourage misuse, a sign above the kiosks warns that the terminals are being monitored in New Delhi.

Original funding for the project came from sources including NIIT, the World Bank, and the Indian and Delhi governments. Mitra estimates that an additional $2 million would help educate as many as 500 million children; he says he is committed to making the kiosk design and plans available without charge to anyone willing to build one.

“The Hole-in-the-Wall experiments have given us a new, inexpensive, and reliable method for bringing computer literacy and primary education to areas where conventional schools are not functional. Such facilities are not meant to replace schools and teachers; they are meant to supplement, complement, and stand-in for them—to help in areas of the earth where good schools and good teachers are, for whatever reason, absent.”

Dr. Sugata Mitra, chief scientist, NIIT

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT