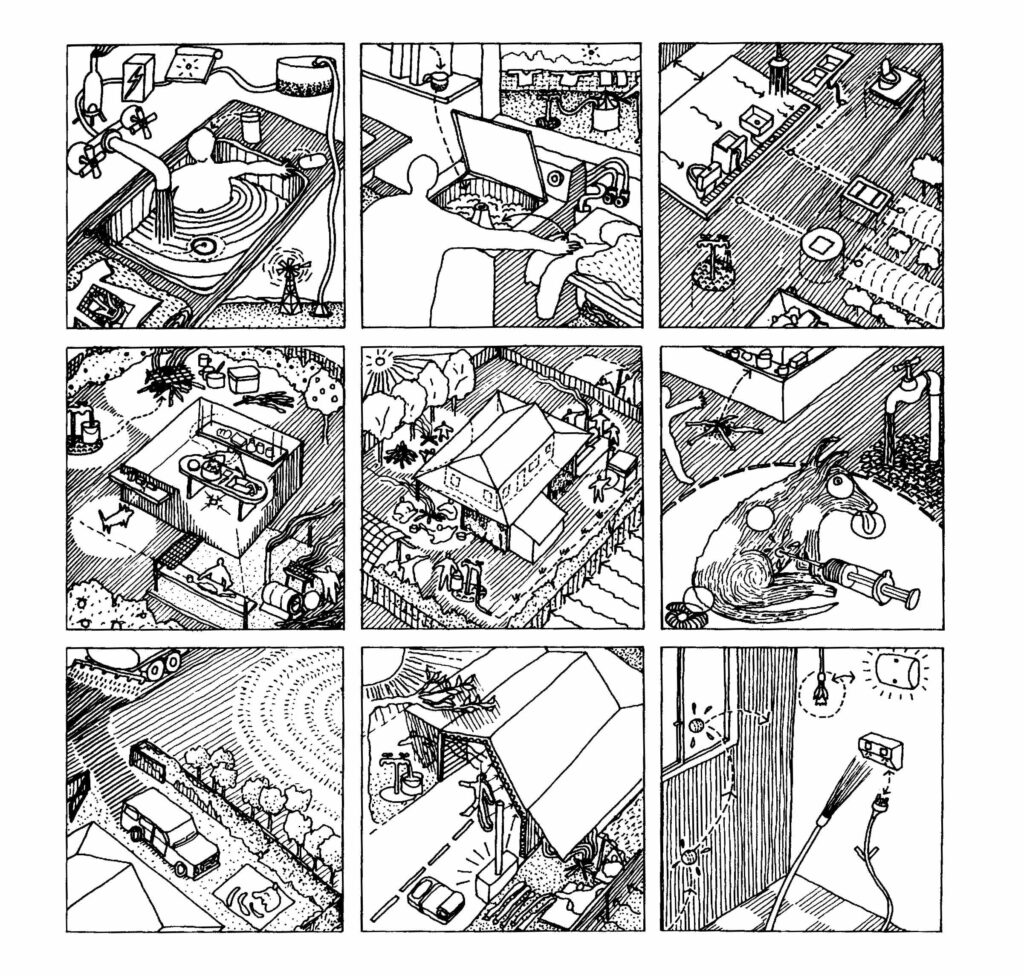

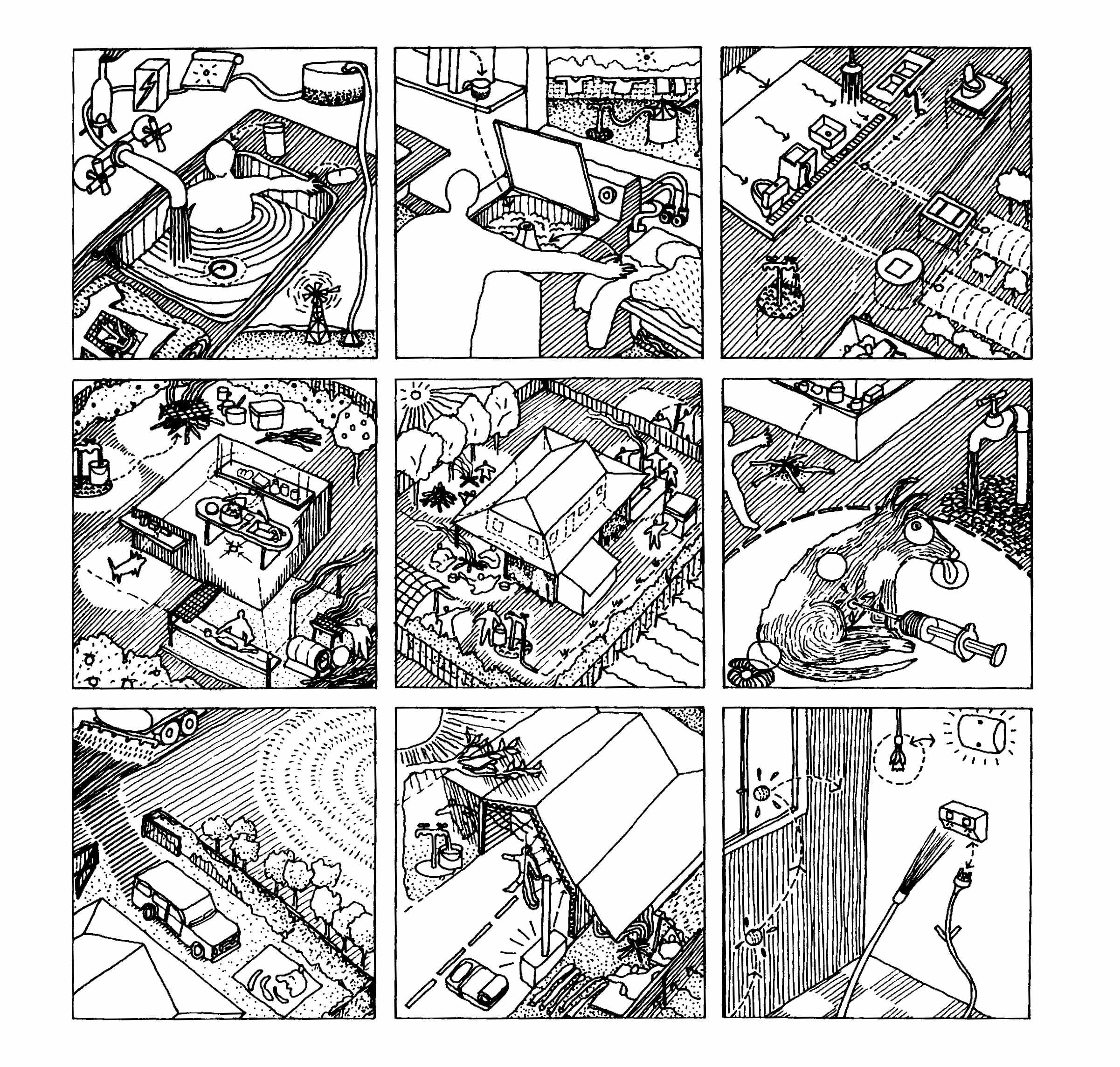

The nine “healthy living practices” identified by the Housing for Health team. Healthhabitat

| Location | Australia |

| Date | 1999–present |

| Client | Indigenous households |

| Organization | Healthabitat |

| Project Coordinators | Paul Pholeros, Stephan Rainow, Dr. Paul Torzillo |

| Major Funding | Federal, local, and state housing and health agencies |

| Number of homes repaired to date | 4,000 |

| Average maintenance costs per house | $2,658–$3,797 |

The Housing for Health project began when an interdisciplinary team realized that health services alone were not improving the welfare of some 3,000 aboriginal peoples living in remote communities in central Australia.

Despite efforts by various health organizations, more than 60 percent of the illnesses being treated at community clinics were basic infectious diseases stemming from poor living conditions.

In 1985 Yami Lester, the director of Nganampa Health Council in South Australia, put together a task force including thoracic physician Paul Torzillo, environmental health expert Stephan Rainow, and architect Paul Pholeros to better understand the causes behind the health issues these communities faced. While previous programs had focused on “education,” attributing the poor health and sanitation conditions in many aboriginal households to poverty or cultural differences, Pholeros and his team members learned that in most cases faulty home construction and poor maintenance were to blame.

“In the first house I entered to commence the survey fi x work, there were two families consisting of 12 people trying to use the two-bedroom house, four of them children under five years of age,” Pholeros recalls. “To make matters worse, there was raw effluent flowing from the direction of the bathroom toilet. After much digging and searching, we found that the toilet bowl had not been connected to a wastewater drainage pipe and was just sitting on the concrete slab! So at the first flush the toilet had overflowed. Government officials and politicians would drive by and remark on the pointlessness of building houses for indigenous people, because they preferred to sit outside the house. [The officials] clearly had never attempted a visit inside.”

Rather than spending more tax dollars on awareness and education, the panel recommended that funds be put to better use toward basic repairs and maintenance on individual houses. Working with health officials and the community, the group identified nine “healthy living practices” in addition to basic safety issues, such as the ability to bathe and wash clothes and bedding, the safe removal of wastewater, and improved nutrition.

The team then evaluated the functionality of each house in terms of how well it allowed families to perform these basic practices. And from the start, the Housing for Health program established a simple rule: No survey without service. Small fixes (everything from repairing showerheads and blocked drains to installing insect screens to updating wastewater systems to accommodate larger households) were done on the spot, larger repairs as soon as possible.

These jobs also provided vital feedback on ways the houses could be designed and built better in the first place, information that Housing for Health has published in a guide to indigenous housing and passes on to architects and contractors working in the community. For example, data collected about bathing facilities such as showers can inform contractors as to which parts of the plumbing work well and which ones do not.

The group also created a training program to teach repair and maintenance trades to community members. The program not only creates jobs but also ensures that local expertise will be available to carry out these tasks in the community. According to Pholeros, Housing for Health, which is now a national program, has employed more than 1,500 indigenous people, “giving the first paid work to many and giving training opportunities to others.”

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT