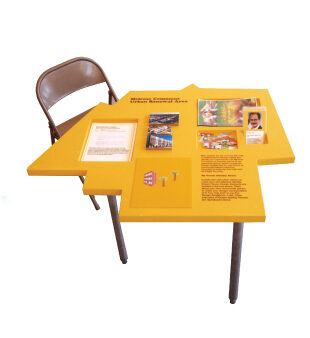

Image above and left: To explain the complex intertwining of design, politics, and finance in federal efforts to remake cities, CUP designed a series of Urban Renewal activity tables and exhibition boards. Each table was made in the shape of the relevant Urban Renewal area and held a series of games and informational devices.

| Location | New York, New York, USA |

| Date | 2003 |

| Design Center | Center for Urban Pedagogy (CUP) |

| Project Organizers | Damon Rich, Rosten Woo |

| Project Team | Danny Aranda, AJ Blandford, Stella Bugbee, Zoë Coombes, Meghann Curtis, Leigh Davis, Beth Lieberman, Andrea Meller, Sam Stark, Celina Su, Oscar Tuazon |

| Partner Organizations | Interboro Institute, Storefront for Art and Architecture |

| Volunteers | James Case, Cynthia Golembeski, Alyssa Gerber, Anette Gallo, Rob Giampietro, Edwin Huh, Jackson McDade, Gaetane Michaux, Jennifer Minnen, Elizabeth Solomon, Lila Yomtoob |

| Major Funding | Brooklyn Arts Council, Center for Arts Education, Storefront for Art and Architecture, City-as-School High School, Parsons School of Design Integrated Design Curriculum, Lily Auchincloss Foundation, Rooftop Filmmakers Fund |

| Cost | $19,353 |

Designed and researched by the Center for Urban Pedagogy, a New York-based nonprofit, City Without a Ghetto examined the urban-renewal programs of the ’50s and ’60s and their effects on the American city.

The project began in 2003 as a curriculum for students at New York’s City-As-School High School and the Parsons School of Design. Under the direction of Damon Rich and Rosten Woo, it eventually grew to become an exhibit that traveled to the Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York, and Mess Hall, Chicago, among other venues.

An immensely successful educational tool, City Without a Ghetto used the Housing Act of 1949 (which gave rise to Urban Renewal, a policy aimed at revitalizing blighted urban areas), as a springboard for discussions of design, urban planning, and low-income housing policies. The act’s use of eminent domain had far-reaching and controversial effects in cities throughout the country. Designers, public policy students, political figures, and community activists collaborated to create the teaching materials, which asked students questions such as: “According to certain narratives of design history, the destruction of Pruitt-Igoe, begun in 1972, forced design into a retreat, abandoning its heroic pose. If we as designers want to effectively relate to politics, what should we take from this example?”

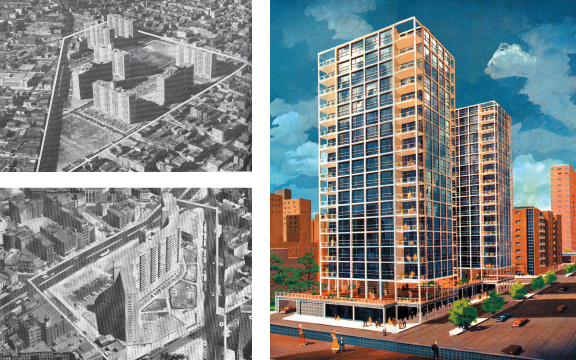

Likewise, the traveling exhibit featured six modules that encouraged viewers to “appreciate how legislation, architecture, finance, popular culture, and social attitudes shape human environments.” It put public-housing programs under a colorful microscope, dissecting the policy and planning arguments that shaped urban renewal. Detailed graphics showed “before” and “after” examples of iconic housing projects and explained how their designs were influenced by legal battles such as Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, the 1966 court case in which a group of plaintiffs argued that the very location of their housing project violated their civil rights. Five tables displayed photographs, timelines, and interactive elements, each table highlighting the history of a different blighted area in New York.

Above all, City Without a Ghetto discussed policy issues in a way that was at once tangible and provocative. Even the project’s name was intended to give students and gallery visitors alike pause for thought.

above and left image: From 1949 through 1974 Urban Renewal programs drastically reshaped built landscapes across the United States.

right image: Futuristic visions provided by architects popularized massive redevelopment, often in the interest of real estate developers. All photographs CUP

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT