The siding of Now House 1 was removed to air-seal the house. Photo: Steve Harjula/Now House Project

Now House before sustainable renovation. Photo: Alex Quinto/Now House Project

| Original Location | Topham Park neighborhood, Toronto, Canada |

| Date | 2005-present |

| End User | 9 households |

| Design Firm | Work Worth Doing |

| Design Team | David Fujiwara, Lorraine Gauthier, Steve Harjula, Harry Mahler, Janet McCausland, Heidi Nelson, and Alex Quinto |

| Engineer | Dave Kalmbach, Patrick Scantlebury (Copperhead Mechanical, Ltd.), Malcolm Stephens |

| Contractor | Martin Osborne |

| Funders | Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2005 Competition), Equilibrium Sustainable Housing Demonstration Initiative, RBC Royal Bank |

| Cost per unit | $50 000 CAD/$51 072 USD |

| Area | 111 sq m/1200 sq ft |

At first glance, this one-and-a-half–story house looks like all the others built after WWII in the Toronto, Canada, neighborhood of Topham Park. However behind its traditional exterior, Now House produces almost net zero energy, generating nearly as much power as it uses. Often sustainable design focuses on new construction. This project recognizes the importance of upgrading existing housing stock to achieve environmental goals.

Local design studio Work Worth Doing entered Now House idea in the Net Zero Energy Healthy Home competition sponsored by Canada Mortgage and Housing in 2005. “This was really an experiment, nobody else was doing zero energy retrofits,” says Lorraine Gauthier, the design team’s project manager. “All the other competition winners were building new zero energy houses.”

Canada’s residential sector represents 17 percent of its energy use and 15 percent of its greenhouse gas emissions, according to a 2010 report by the Office of Energy Efficiency, Natural Resource Canada. Now House takes advantage of the minimal embodied energy required for retrofitting existing housing and avoids the high embodied energy, energy consumption, and emissions associated with the manufacture and transportation of new materials required for new construction. After the success of the first Now House, the firm completed eight more near-zero energy retrofits around Ontario.

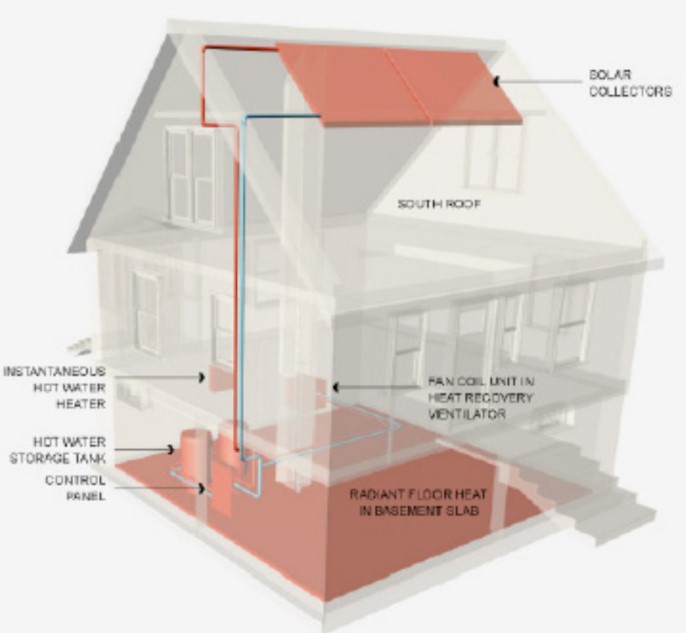

Now House uses solar energy to heat the house and its water. Image: David Fujiwara/David Fujiwara Architect

A data-based process of measuring and upgrading is the modus operandi of the project, which starts by studying the baseline performance of a house. The first goal is to reduce the energy load of the house through basic fixes like air sealing and upgrading windows, adding insulation, and installing energy efficient fixtures, lighting and appliances. Next, the house is reassessed to measure the effectiveness of the upgrades. This data is used to determine the extent of work needed for the HVAC and mechanical systems. Solar electric and hot water systems are installed to reduce the gas and electrical needs as a final step.

The result is a near-net ZEROW House that produces as much energy as it uses. The house is not off-the-grid, but rather the energy it produces is fed back into the power grid. For example, the first Now House uses a grid-tied system that feeds power into the Ontario power grid. It also falls under a “feed-in” tariff, a utility program in which the power company buys back all power produced by the house at 80 cents per kilowatt-hour while supplying the house with power at approximately 8 cents per kilowatt-hour.

A Now House’s success is established by measuring energy consumption meters and comparing pre- and post-retrofit energy bills. This helps document numerous smaller interventions that can be extremely effective in improving sustainability. For example, the fifth Now House received minimal upgrades like air sealing and insulation, new appliances, compact fluorescent lights , and low-flow water fixtures. It went from a Canadian EnerGuide for Houses score of 55 to a score of 74, where 100 equals a net ZEROW House.

The small size of the houses impacts the time it takes to recoup the investment of upgrading through energy savings. “If we doubled the size of the house, which would be more the norm of recent houses, the payback would be a lot faster,” Gauthier says. However, renovating larger houses at a better payback rate is not necessarily more efficient because of the materials and energy it takes to complete the renovation.

Work Worth Doing discovered that the cooperation of the homeowner is essential. “One family, before the retrofit, used twice as much energy as the other families; and they still are,” Gauthier says. “However we have made an impact on reducing their overall use by 30 percent.” Gauthier cautions that this is an evolving process and not a “silver bullet for the answer to all retrofits.”

Now House Project is trying to expand its efforts, but its small size makes it difficult to manage projects at a distance. The design team is working to distill what they have learned into a basic system that could be made available online and through a national home retailer, according to Gauthier.

left image: Workers install insulation to the exterior foundation walls. Photo: Heidi Nelson/Now House Project

middle image: Spray foam insulation is added to the exterior walls. Photo: Heidi Nelson/Now House Project

right image: Solar thermal panels (on left of roof) provide how water and heating. Solar photovoltaic panels (on right) produce electricity that is sold to the local power company. Photo: Heidi Nelson/Now House Project

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT