view of new housing units

| Location | Iquique, Chile |

| Date | 2002–2005 |

| Client | Regional Government of Tarapacá, Chile-Barrio |

| End Client | 93 illegal households |

| Partner Organizations | Pontifi cia Universidad Catolica de Chile; Serviu/Seremi Iquique |

| Design Center | Taller de Chile |

| Design Team | Alejandro Aravena, Alfonso Montero, Tomas Cortese, Emilio de la Cerda |

| Public Policy Consultants | Andrés Iacobelli, Elena Puga |

| Engineers | JC de la Llera, Carl Lüders, Mario Alvarez, Tomás Fisher, Alejandro Ampuero, Jose Gajard |

| Major Funding | Ministry of Housing and Urbanism, Chile-Barrio Program |

| Cost | $7,500 (including land) |

| Area | 430 sq. ft./40 sq. m |

| Website | www.elementalchile.org |

Most designers find solutions to policy limitations as a matter of course; rarely are they inspired by the limitations themselves.

In the case of this innovative housing project by the interdisciplinary design team Taller de Chile, a change in housing policy inspired them to turn to their drawing board and prompted them to invite other architects to do the same. The result was a design-based solution to a problem that has vexed housing agencies throughout the world for decades: how to replace sprawling squatter settlements in urban centers with dignified, higher-density, low-income housing without creating vertical slums.

In 2002 the Chile-Barrio program, which works to upgrade the country’s illegal settlements, changed its housing policy. Under the existing policy families were defaulting on loans. Rather than giving families loans and subsidies worth $10,000, policy makers decided to offer them mostly subsidies worth $7,500. The new program, “Dynamic Social Housing Without Debt,” was intended to increase the number of beneficiaries without increasing the financial burden of families.

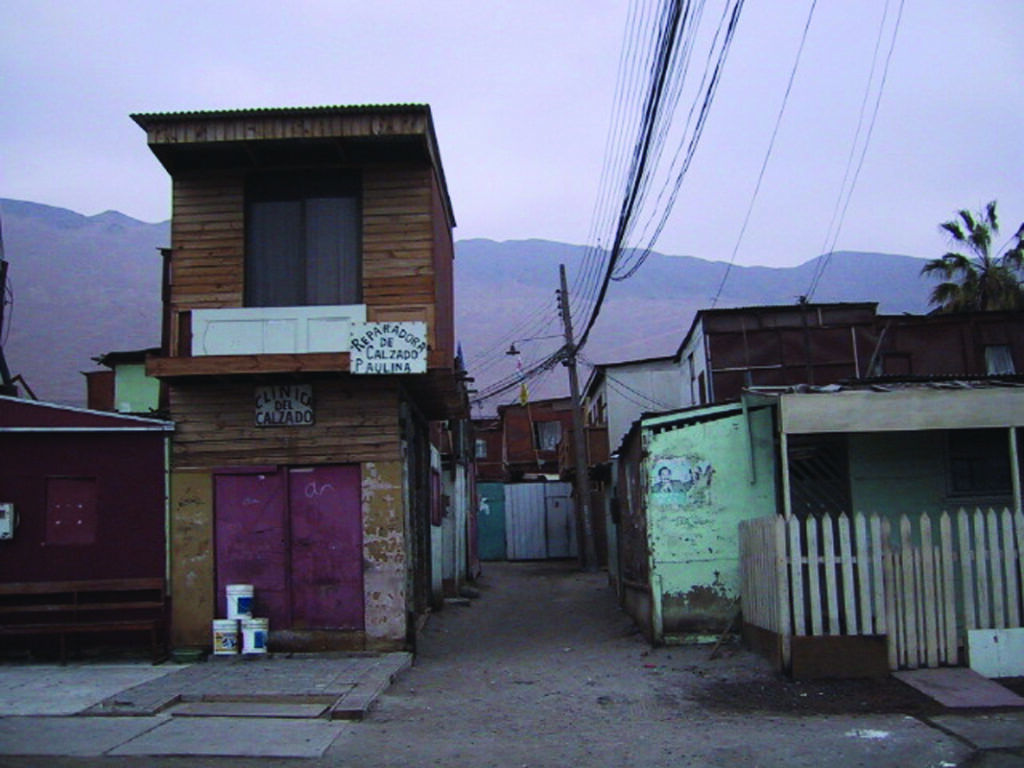

Typical residential areas in Quinta Monroy, an informal settlement in Iquique, Chile, prior to the Elemental housing initiative.

But the change posed a number of challenges for the housing developers and nonprofit groups charged with implementing it. Chief among them was the problem of building a structurally safe home for less than $7,500—including the cost of land—without pushing families into the periphery of the city, where they would be far from jobs and support networks. Hoping to address this challenge, the ad-hoc team of architects, engineers, contractors, and public-policy experts of Taller de Chile designed a pilot program to resettle 93 families from Quinta Monroy, a 30-year-old illegal settlement in the center of the port city of Iquique, into new housing on the same site as their original homes.

The Chile-Barrio program initiated the project and contracted the Pontificia Universidad Catolica, where a number of Taller de Chile team members were based to undertake it. Design was constrained in several ways: The new housing had to be built on the site of the old settlement where land is more expensive, leaving less money for construction. It had to provide each family with the largest home for the subsidy provided. It had to enable occupants to easily build additions as they could afford them. And all this had to happen within a site plan that would allow the new development to grow in an orderly way. Most important, in order to ensure that the project could be replicated, the housing scheme had to be feasible within the existing policy framework—despite its limitations.

Collaborating with families in a series of workshops, the design team explored several alternatives before settling on this duplex solution. By building alternating single-story and double-story units, the scheme allows families to expand vertically rather than horizontally, thereby allowing for greater density without overcrowding. In an effort to ensure “orderly” growth, the team chose a U-shaped site plan that clearly demarcated common spaces and allowed for parking, roads, and walkways between residential clusters. Construction took a year and was completed in early 2005. During construction families were relocated to temporary housing. Within four months of their return families had already begun adding to their units—a move the designers interpreted as a sign of the project’s success.

In tandem with the pilot project in Iquique, the team also hosted an international design competition in 2003. Called Elemental, it invited designers to explore alternative solutions to Chile’s new housing policy. A jury of architects, housing experts, and policy makers from the Ministry of Housing selected seven winning designs. The teams behind those designs are now working with communities and nonprofit organizations at seven other sites to help more families take full advantage of government housing subsidies using the same participatory model.

The resulting new housing in Quinta Monroy, Iquique, Chile four months after construction with additions added by the residents.

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT