| Location | Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa |

| Date | 2006-14 |

| End User | Approximately 200 000 people in four neighborhoods of between 25000 and 50 000 residents each |

| Implementing Agency | City of Cape Town, Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (German Development Bank) |

| Planning | AHT Group, SUN Development PTY |

| Associated Firms | ARG Design, Charlotte Chamberlain & Nicola Irving Architects, Jonker & Barnes Architects, Macroplan Townplanners, Masimanyane Community Participation, Partners for Impact, Naylor & Van Schalkvwyk, Talani Quantity Surveyors, Tarna Klitzner Landscape Architects. |

| Additional Consultants | Masimanyane Management Consultancy |

| Funders | City of Cape Town; German Development Bank; provincial and national South African funding; private sector funding totaling about 400 million South African rand/$57 million USD |

| Program Cost | 400 million South African rand/$57 million USD |

Khayelitsha, a township of Cape Town, South Africa, was established in 1985 during the apartheid era. It has experienced some of the highest crime rates in the Western Cape. In 2003, the area reported 358 murders, 588 sexual crimes and more than 3000 incidents of violent assault according to the Crime Information Management Centre of the South African Police Services. At night, it was unsafe to return from work, and the township, which has few paved roads or formal structures, was difficult to patrol.

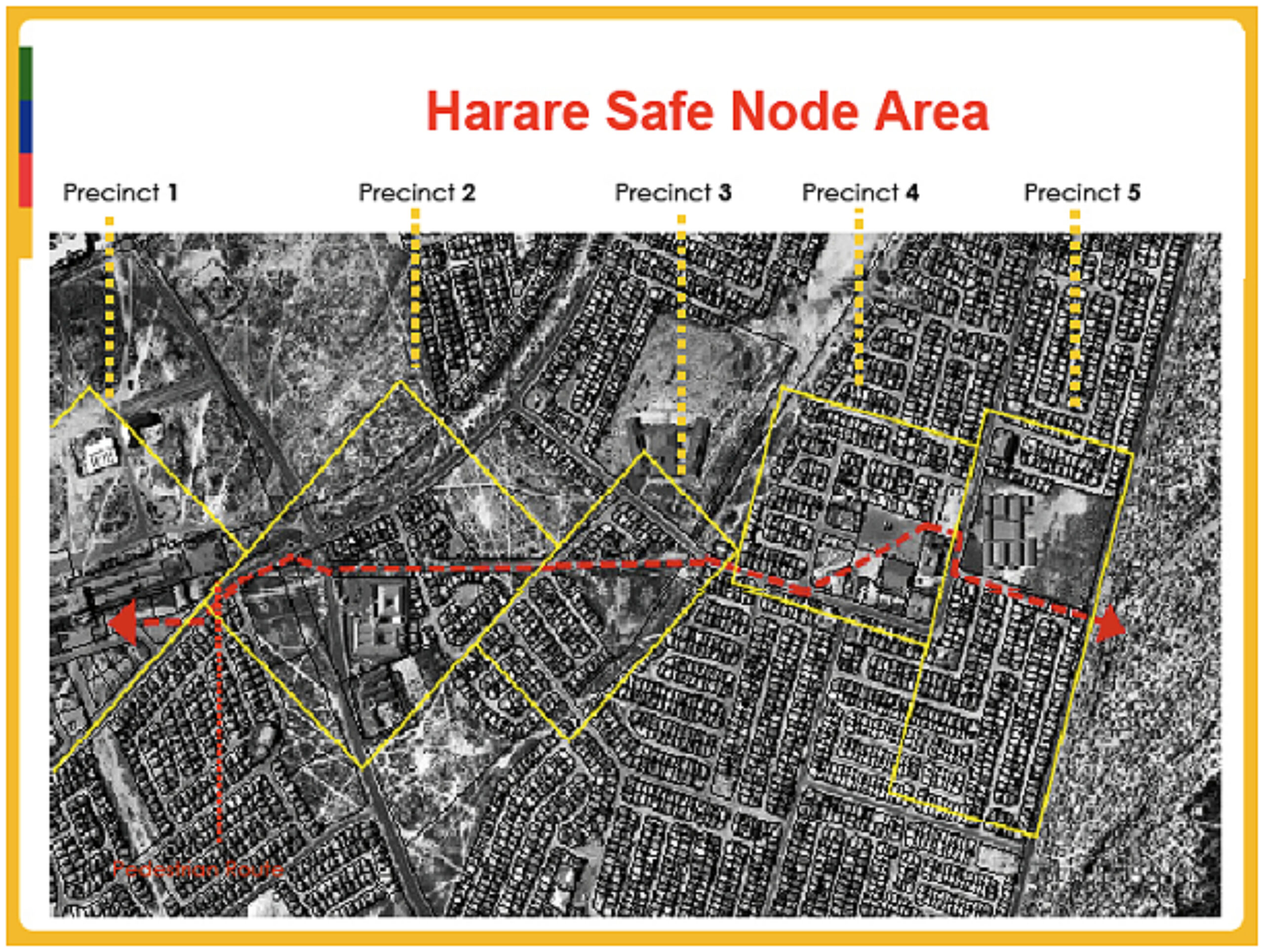

Recognizing that the many factors leading to the area’s high crime rate were often interlinked, the city of Cape Town, German Federal Ministry for Economic Development, South African Treasury and Khayelitsha Development Forum called for the creation of a neighborhood-wide strategy. An initial baseline survey identified the top three crimes, which were murder, rape and robbery. However, rather than using traditional urban planning methods and tools, the team mapped data using a geographic information system (GIS) to identify areas prone to crime and develop social and architectural interventions.

The result was a $57 million USD, five-year pilot program called Violence Prevention through Urban Upgrading. The program’s commonsense approach resulted in a 33 percent reduction in murder in 2009 in Harare, the first area where it was implemented, with almost no incidents of murder reported in public spaces. Public perceptions have changed as well, with 48 percent of people surveyed in 2011 reporting they felt safety was improving compared to only 21 percent in 2007 when the program began.

Specifically, the program focuses on reducing crime by identifying where crime takes place and making small, but targeted interventions at the spots where crime is most likely to happen (referred to by VPUU as “Hot Spots”). These interventions may be as small as removing vegetation that predators could use as cover or as large as a community center and park.

Interventions (referred to as “Active Boxes” by VPUU to connote the concept of activating a public space) are strategically located so that pedestrians are always in view in high crime areas. “The Active Boxes are a good illustration of how an integration of built, social and place management interventions can transform perceived dangerous spaces into positive and owned spaces,” explains Michael Krause, director of Sustainable Urban Neighborhoods Development, the implementing partner of VPUU.

The program sets strict standards for architects designing interventions and designs are reviewed by a community board. “The buildings don’t have hideaway corners or nooks where people can hide and observe as you approach the building,” says Cedric Daniels, manager of urban design for the city of Cape Town. “This follows the very basic principle that if a criminal knows he is being observed, can be identified and can get caught for a crime, he is less likely to perform a criminal act.”

In addition to changes in the built environment, investments are made in social programs such as neighborhood policing and rape prevention in the same areas.

One of the projects that illustrates VPUU’s holistic approach is the new Ncomu Road Urban Park. At one corner of the park is the Ncomu Road Urban community building designed by the firm ARG Design. Anchoring the opposite corner is the new Football for Hope Centre, also designed by ARG Design with Architecture for Humanity. Operated by Grassroots Soccer the Football for Hope Centre and adjacent football pitches offer sports and youth leadership training as well as HIV/AIDS education.

The park’s buildings are not enclosed by fences or gates as is typical in South Africa. Instead, they engage with the street. “This is intended to invite residents to freely use the variety of spaces, to interact and engage with the programs being offered,” says Verena Grips, a project designer for both centers. At night, a caretaker guards the new park from a second story flat with 360-degree sightlines, offering “eyes on the street” and creating a place where residents can seek help if they feel threatened. The park also includes a playground for young children and is navigated by well-lit, paved pedestrian pathways. Throughout the area, similar “Active Boxes” have been built or are planned to ensure safe passage for residents.

To date, there are a total of 10 completed projects that aim to reduce crime in seven crime Hot Spots. VPUU’s success in Harare helped it secure funding until 2014, and the city plans to expand the program throughout the township.

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT