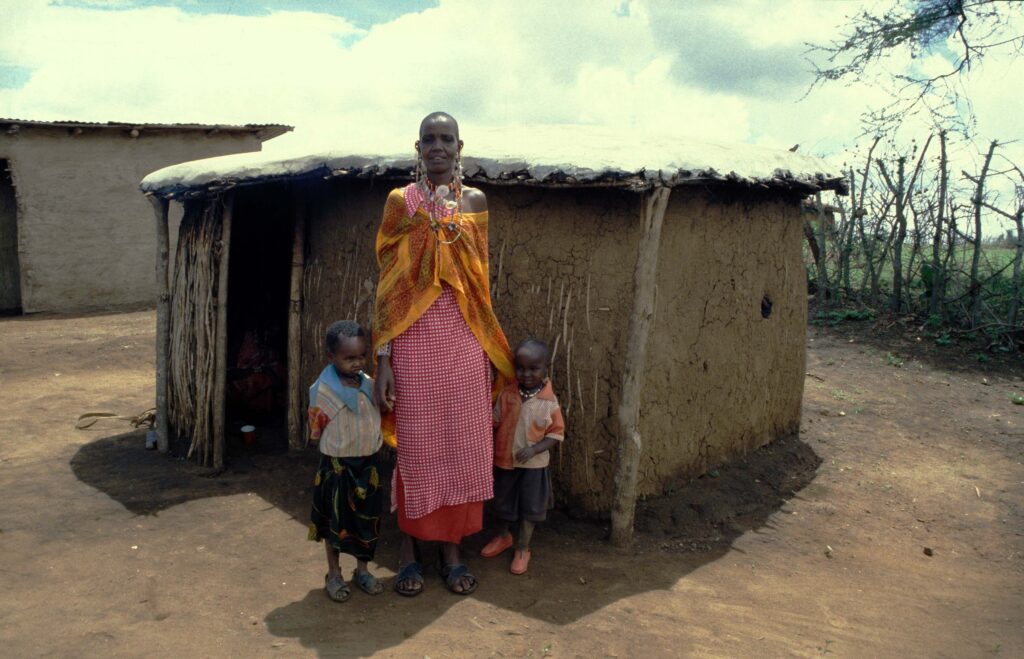

Maasai women compact rammed-earth walls. ITDG/Neil Cooper

| Location | Magadi Division, Kajiado District, Kenya |

| Date | October 1999–April 2002 |

| Client | Arid and Semiarid Lands Program |

| End Client | Maasai women |

| Design Center | Intermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG), East Africa |

| Design Team | Sharon Sian Looremetta, the Maasai community |

| Engineer | Edward Lein Marona |

| Construction Manager | Sirenche ole Kanambase |

| Additional Consultants | Dr. Nick Hall, Amon Ng’ang’a |

| Major Funding | Danish Embassy |

| Cost | $721 per house |

| Website | www.itdg.org |

The Maasai of Kenya are probably one of the most well-known indigenous tribes of East Africa.

Unlike most that organized into kingdoms, the Maasai never abandoned their nomadic lifestyle, settling instead into clans and subtribes. Their housing consisted primarily of huts known as inkajijik, which are plastered with cow dung. Due to increased urbanization and the declaration of game reserves such as the Maasai Mara and the Serengeti in recent years, however, the tribe’s ability to graze its cattle over large areas has significantly diminished, resulting in a less nomadic lifestyle—and the need for new permanent housing.

As of the late 1990s a rapidly growing population of approximately 120,000 Maasai lived in an area of 8,500 square miles (22,000 sq. km) in Kenya’s Kajiado District. In 1999 ITDG in Kenya received a request for assistance by the Arid and Semiarid Lands Program to address the area’s growing housing crisis.

Unlike the practice in other tribes, Maasai women maintain a prominent position within the culture and are in charge of housing construction and maintenance. ITDG’s role was to work with local women’s groups to give support in developing shelter strategies and new technologies.

Left image : A woman plasters her roof with dung in the traditional method. ITDG

Right image: Mrs. Silole Malipe ene Mpariya built her own ferro-cement skin roof according to ITDG’s methods. The new ferro-cement roof requires less maintenance. ITDG/Neil Cooper

Women with their new ferro-cement roof, which collects rainwater and channels it into a cistern also made of ferro-cement. ITDG/Lucky Lowe

At a workshop the women presented their ideas on housing design and construction. Their main concerns included the need for natural lighting and ventilation (most inkajijik have no windows and only one door opening). Smoke from cooking fires gets trapped in the houses and is a major contributor to respiratory complaints. They wanted to avoid time-consuming maintenance (the traditional plaster of dung, mud, and ash needs constant attention, especially during the rainy season). And they wanted more space (inkajijik have such low ceilings that adults are unable to stand upright inside).

“I used to spend a lot of time fixing my walls and roof, and the trek to get water from long distances was very tiring. When we all have houses like mine, we shall be able to find solutions to other problems that face us.”

Nolari Nkurruna, member, Naning’o Women’s Group

To address these concerns ITDG proposed three different housing options, each of which combined traditional building methods with new techniques and materials. The first option involved building with rammed earth; the second option was constructed from soil blocks stabilized with a small amount of cement; the third and most popular option made use of ferro-cement, cement reinforced by chicken wire.

To replace the traditional dung-based plaster, the ITDG—in a trial-and-error process with the Maasai Rural Training Center—found that it could use ferro-cement to create a more permanent and weatherproof roof, as well as walls and water-collection jars. It was a small but significant change.

Because the new roofs were stronger and more durable, windows and living spaces could be enlarged, addressing many of the health problems associated with the traditional inkajijik. The new technology also enabled rain collection from the roofs, which meant women didn’t have to travel long distances to get water.

Since the project began more than 2,400 houses have been built, and the region has seen a significant drop in the incidence of respiratory disease, malaria, and other illnesses. Whereas maintaining their homes and collecting water had once been taxing and time-consuming activities, the women now have time to spend on other pursuits, including starting their own small businesses—proving the strong ties between sustainable housing, economic prosperity, and independence.

Maasai women build a home using rammed earth. ITDG/Neil Cooper

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT