| Location | Oakland, California, USA |

| Date | 2005-12 |

| End User | 550 residents with incomes between 0 and 60 percent of Area Median Income; Project Access |

| Implementing Agencies | Oakland Housing Authority, Habitat for Humanity East Bay (Kinsell Commons) |

| Design Firm | David Baker + Partners Architects |

| Structural Engineers | OLMM Consulting Engineers |

| Electrical | FW Associates |

| Mechanical/Plumbing | Guttman + Blaevoet, SJ Engineers |

| Contractor | Cahill Contractors |

| Development Consultant | Equity Community Builders |

| Landscape Architect | PGA Design |

| Lighting Designer | Horton Lees Brogden |

| Civil Engineer | Sandis |

| Major Funders | State of California MHP Loan State of California Infill Infrastructure Grant; 4 percent Low-Income Housing Tax Credits; 4 percent Tax Exempt Bonds; City of Oakland Redevelopment Loan; Oakland Housing Authority Loans; Citibank Loans; Alameda County Loan; Environmental Protection Agency Brownfield Cleanup Grant; Federal Home Loan Bank of SF-AHP; Deferred Developer Fee |

| Financial Partners | Citi Community Capital, National Equity Fund, State of California Housing and Community Development Department Multifamily Housing Program, State of California Housing and Community Development Department Infill Infrastructure Grant Program, City of Oakland Redevelopment Agency, California Debt Limit Allocation Committee, California Tax Credit Allocation Committee, US Department of Housing and Urban Development, US Environmental Protection Agency |

| Construction Cost | $232 USD per sq ft |

| Cost per unit | $431 000-$439 000 USD |

| Total Development Cost | $75.2 million USD (excluding Kinsell Commons) |

| Site Area | 7.91 acres (5.33 buildable acres) |

| Building Area | 23 960 sq m/255 000 sq ft |

| Number of Units | 157 apartment units; 22 single-family dwellings |

David Baker (top) and Daniel Simons (above). Photos: Brandon Loper/David Baker + Partners Architects

Interview:

David Baker + Partners Architects: David Baker, Daniel Simons

Oakland Housing Authority: Bridget Galka

Developed by the Oakland Housing Authority, Tassafaronga Village is the first affordable-housing project to achieve a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Neighborhood Development Gold Certified Plan, as well as LEED for Homes Platinum certification for all dwellings.

The project was developed by the Oakland Housing Authority and designed by San Francisco-based architecture firm David Baker + Partners Architects.

The firm is known for combining contemporary design with social responsibility and sustainable practices. To learn how the project came together, we talked about the design process and the benefits of LEED certification with Bridget Galka, senior housing program development manager in the real estate development department of the Oakland Housing Authority, and project manager for Tassafaronga Village, principal David Baker, FAIA LEED AP and project architect, and Daniel Simons, AIA LEED AP.

Children play in front of the Tassafaronga townhouses. David Baker + Partners

Why do you give a damn about design?

DS: I grew up in Berkeley, where there are a lot of radicals who are trying to change the world, but a lot of them are really ineffective. I found that people who are really effective at doing something good, also care deeply about something completely independent of the benefit that it has to society. Design was clearly the thing I was really passionate about.

DB: At one point my dad read the autobiography of Frank Lloyd Wright and started building solar houses, which is where I was born and raised. He almost got published in Arts & Architecture magazine, until they figured out he didn’t have a high school degree. At about 8, I decided to be an architect, but I went to school during the Vietnam War, and became a protestor and a draft resistor instead. Eventually I became a revolutionary and hitchhiked to Berkeley. I had completely forgotten about design at that point. I started in energy, doing solar projects. Then I won a competition for affordable housing in Sacramento (California, USA), which was followed by a few projects early on in the affordable housing industry. All of a sudden I was an expert because I had done a few projects. I didn’t have a plan that I was going to go to work in the affordable housing industry, because when I was in school there was no such thing, so it was a little bit accidental.

How did the affordable housing industry get started?

DS: For a long time it was housing authorities and HUD (Housing & Urban Development). A lot of the housing done under HUD and the housing authority auspices was good design but it didn’t work, mainly because it didn’t connect across the breadth of the spectrum, the client, operations, all those things. Then they decided in a quasiconscious decision that it was not effective and that they should outsource it to nonprofits through tax credits and grants instead of directly funding it. Affordable housing became something that was really great to design because we had really great clients.

How has the affordable housing industry changed?

DS: The first affordable housing project we did, the clients had the notion that they should look ordinary. There are still a lot of affordable housing people that think that affordable housing shouldn’t stand out, that it shouldn’t be wonderful or an incredible place to live necessarily. They think that building it with low construction costs is the goal. We definitely don’t feel like that.

DB: It’s more true of other parts of the country, than California, where there is a lot of affordable housing bureaucracy and they still treats design like a luxury. Architects have to fight really hard to put a window in a corridor, and somebody at this bureaucracy is saying, “We don’t allow windows in corridors because they leak, people break them, and people fight about opening them.” They have a whole list of reasons.

DS: We brought the highfalutin notion of design back and kept talking to our clients about it. We had to do it gradually over the years. They were very resistant in the beginning, but in the last 30 years the housing market has changed for the better. We’ve been lucky to be a part of it.

When you are embarking on a LEED certified project, who starts the conversation about sustainable design?

DS: Well, for Tassafaronga Village, the Oakland Housing Authority wanted to select an architect that had experience doing green building, but they didn’t necessarily know what that meant and it could have ended there.

DB: Right, they didn’t come to us and say, “Please do a LEED for Homes, LEED Neighborhood Development, high-level rating project.”

How did the Oakland Housing Authority select Daniel Baker + Partners to develop Tassafaronga Village?

BG: We are a public agency so we had a competitive process. We put out a Request For Proposals (RFP). It was published in the newspaper and mailed to all of the architectural firms in the area.

The RFP included a very clear process of evaluation and scoring criteria that included qualifications, past performance, green building strategies, understanding of the project, cost and efficiency, and Section 3 hiring of low-income residents. The scoring criteria and evaluation process was published with the RFP so everyone knew how the proposals would be scored. We received 11 proposals from very qualified firms. We interviewed two firms based on the scoring, and chose David Baker + Partners Architects.

David Baker’s proposal played on the industrial edge of the site. The plan hid higher density within a development that looked exciting. We had one criterion that asked applicants to explain their vision for green and sustainable design. Back in 2005, it wasn’t yet common for architecture firms to have LEED AP professionals. David Baker’s response to that question kicked them up a notch.

DB: We knew the LEED Neighborhood Development Pilot Program was going on. At one point we said, “Hey Bridget, is this going to be green? There is this new thing called LEED Neighborhood Development and we should go after it.” Because it was a pilot program it was quite inexpensive. When we figured out the cost, Bridget said, “We’ll pay the fees if you manage the process.” We didn’t have a third party green consultant, we just did it. So we went from no certification to LEED-ND Gold and all the homes being LEED for Homes Platinum.

Before: The existing public housing project was declared “severely distressed”, paving the way for the Oakland Housing Authority to develop a new housing complex. Image: David Baker + Partners Architects

The new site plan includes the adaptive reuse of an existing building and an additional parcel of industrial land. The project integrated into the surrounding neighborhood repairing connections through new streets and pedestrian pathways. Image: David Baker + Partners

These projects require complex financing, given David Baker + Partner’s experience in affordable housing, do you help your projects find financing, or tax credits and such, to offset the costs of doing sustainable design?

DB: No, never. Usually these projects have 10 or so funders, and the people who do that have a different talent than we do.

DS: Maybe if we know there is a certain amount of money available for some sustainable feature, we’ll make a suggestion. Alameda County (California, USA) has grants for sustainable development. If we have a client that is unfamiliar with them, we’ll put them in touch with the right people.

How was Tassafaronga Village financed?

BG: We started the planning process by preparing two HOPE VI grants. Originally there were 87 public housing units at Tassafaronga that were deemed to be “severely distressed,” which is a requirement to be eligible for HOPE VI funding. We submitted the first Hope VI application in 2005 and were unsuccessful. It is a very competitive process and the Oakland Housing Authority had previously been awarded three large HOPE VI grants in 1998, 1999, and 2000. By the time we submitted the first application for Tassafaronga the HOPE VI application criteria had been modified to favor smaller public housing authorities with no HOPE VI grants.

In order to apply for HOPE VI funding you must have a lot of resident and community meetings to prepare the application. We had five or six meetings in the community but our application was unsuccessful; so, we tried again the next year and had another five or six meetings. As a result of the HOPE VI planning process the vision for the site was taking shape and we were getting closer to having the site plan we ultimately developed when we submitted our second HOPE VI application in early 2007.

By participating in the many meetings, the residents got their hopes up and were generally excited to move away, have all their relocation costs covered, and maintain the opportunity to move back into a nicer development. We had invested in creating a viable revitalization strategy but we didn’t get the second HOPE VI grant either. Our Board of Commissioners had to make the decision to either continue to apply for HOPE VI grants or try to find another way to finance the revitalization.

The best alternative to HOPE VI was replacing the public housing units with Section 8 Project-based Vouchers. The Section 8 rental subsidy allows us to serve the same very low-income households, but with Section 8 you get enough operating income to pay down debt because the Section 8 Voucher rent is higher than the public housing unit operating subsidy. We presented the option of replacing public housing units with the Project-based Section 8 Voucher units as a way to maintain the same level of affordability but tap into higher rental income that would allow us to obtain a permanent loan. The board decided to proceed with the Project-based Voucher approach, so, in fact, there are no public housing units at Tassafaronga now but there are actually more units for very low-income households.

In addition to the loan on Section 8 rental income, the Oakland Housing Authority had resources from years of good fiscal management that we called our reserves. When the authority does these large revitalization projects, we commit a part of the reserves as gap financing in order to raise additional funds from other affordable housing sources. We contribute our own equity to be more competitive. Between the Project-based Vouchers and our equity, we were able to raise financing from the typical sources, such as state tax credits, tax-exempt bonds, city of Oakland redevelopment funds, state of California bond funds and Federal Home Loan Bank affordable housing program financing. The state of California had an Infill Infrastructure grant program to pay for the cost associated with developing infrastructure associated with urban infill housing. We were awarded money from that program. We also got some money from the Environmental Protection Agency for brownfield cleanup and we got some money from Alameda County.

constructed by Habitat for Humanity, is linked to the main apartment building at Tassafaronga by a “Village Green”. Image: David Baker/David Baker + Partners Architects

The courtyard of the main apartment building at Tassafaronga Village was built over a parking garage. Image: David Baker/David Baker + Partners Architects. Sketches by David Baker

Can you walk us through the design of Tassafaronga Village?

DB: There were originally 87 units at Tassafaronga on a 5.5-acre site that were all public housing under the Oakland Housing Authority. Now it is 7.5 acres. They added an abandoned industrial site and an abandoned pasta factory, which allowed them to link a school and a library and complete the street grid.

Tassafaronga now has 157 units plus 22 Habitat for Humanity houses. That’s a big jump in density, even with the added acres, which is really to the Oakland Housing Authority’s credit.

We scrambled to make sure it was not a homogenous project. We had apartment buildings, which is one typology, townhouses, which are another typology, then we renovated the pasta factory with supportive housing, which is a third typology. We also had the Habitat houses. So we worked to integrate the Habitat houses throughout project.

Oakland Housing Authority split the project into two phases. We did construction drawings for the first phase, then did the second phase. Phase Two was basically the Pasta Factory renovation. That was a big enough piece to break out, which helped the financing.

top left image: Rendering of the proposed Tassafaronga Village development. Image: David Baker + Partners Architects

top right image: Rendering of the abandoned pasta factory that was repurposed to hold supportive apartments and a medical clinic. Image: David Baker + Partners Architects

above image: The completed development Tassafaronga Village. Photo: Brian Rose/David Baker + Partners Architects

Given the kind of budget constraints you face on a project like this, are there typically competing needs between the occupant and the agency developing the housing?

DB: If you ask the occupants a lot of them would say, “Well, we want a 4000-square-foot house…” but I think the nonprofits work in a pretty constrained and realistic world of financing and zoning. It’s good to understand the occupants’ needs, but there are just a lot of rules and constraints that our clients need to navigate.

How often does the design team talk to the people that will be living in the housing projects that you design?

DB: We never talk to the people that will live in them because nobody has any idea who they actually will be. So, it’s impossible to talk to them. Most nonprofit developers don’t have good post-occupancy programs either, where they really go and systematically talk to people [about the design]. We’ve done it quite a bit, informally, and it’s totally amazing.

DS: If we do community meetings there may be some residents that might be there, and sometimes the nonprofits will have people review the design.

DB: So when we’re designing, we try to channel the residents. We try to make a place where we would like to live. The idea being that we’re not too terribly different from other people.

So, what have you learned over the years about designing a building that better serves its residents?

DS: There are dumb things that are easy but a lot of people forget. There are a few spaces in every apartment building that people are going to be in outside of their own unit. They’re going to be doing laundry, getting their mail, walking down the corridor to the front door. These spaces are opportunities. If you don’t treat these spaces as after-thoughts, they provide opportunities to meet their neighbor, to sit outside and read a book, or bring some daylight into a corridor.

DB: We’re trying to green stairs so that people don’t use the elevator as much. If we can [create] a connection to the outdoors, maybe an outdoor barbeque, that’s huge. The other thing about affordable housing is that there are more kids. There is a need for more community space. We think a family-oriented kids classroom is a really good idea. People can set up ad hoc childcare. If it’s designed to be acoustically separate, kids can have music lessons or play in a punk band.

DS: People think a community room will get used once a month to gather all the residents and give them info. We were talking with the developer of a project we did 10 years ago, and they said the community room is booked both Friday and Saturday three months in advance. Residents hold weddings, quinceañeras—all kinds of things.

When you are designing affordable housing, if you do include a nice mailroom, a nice community room, and a nice lobby, we’re only talking about 5 percent of the square footage of the building—and a lot of that isn’t good space for a unit because they are odd leftover spaces or next to a mechanical space. So, for your overall budget, if you’re adding fancy cabinets to every unit, you are never going to be able to afford it. But if you take a few spaces that are key to the building community and make them more dramatic, you’re not going to break your budget.

Do you have much latitude in suggesting new ideas?

DB: We work under the premise of having a lot of ideas. Most recently, with Mercy Housing, they kept saying, “Yes, yes… ,” until we got to the chickens. Then they said, “No, no we can’t do chickens,” which is probably reasonable. We even said, “Just chickens, no roosters!” but they still said no.

Your projects are known for engaging the streetscape well. What are the ways that you work to enhance pedestrian friendliness?

DB: It’s really important to make your edges as active as possible. That is easier said than done. Projects have requirements that take up space, like transformer rooms, exits and garage entries. In an urban context it is pretty common to have the entire facade filled. It’s really good to look at precedents. For example, when you are designing retail, looking at retail that works.

DS: Yeah, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

DB: But it’s hard to copy the wheel, for a lot of people, and it’s really hard for architects. There are a couple of area’s where it’s great though, a walkup storefront, or a bike rack. You’d be amazed at how few architects locate a bike rack so that you can lock a bike to it.

We also try to create a hierarchy of open space. We have what we call a Feng Shui-compliant entry sequence where you enter into a courtyard from an urban area so that you’re not just going through the door into a lobby or to your mailbox.

Permeability is important too. There is a tendency to [design] a doughnut. Massive buildings that are hollow on the inside. They have a very nice courtyard but you can’t see the courtyard from the outside.

We include daylight throughout and a lot of open space. It’s not actually more expensive. People love it. You don’t want to be afraid to think up new ideas, but you don’t want to forget the good ideas from the past either. A nice place for people to sit and read their mail with a recycle bin, for example, which is a pretty dumb concept, but it’s amazing to pull it off.

How do you manage the costs of LEED/green design?

DS: My standard line, which I think is totally true, is if you want to do the cheapest building possible, then absolutely, green design is a little bit more expensive. If you’re doing a nice building anyway, because you’re going to be managing it for the next 50 years, then at that level, you have a certain amount of discretionary spending. If you decide to use that discretionary budget on sustainable features, then you shouldn’t really be spending any more.

DB: If you just took all the fake bricks off of a project you could make it LEED Platinum. Typically, there are multiple inefficiencies that are hard for the client to pick out. I’ve gone into projects, and said “Wow, those chairs are $600 USD each…” I guess the client didn’t look at that particular invoice.”

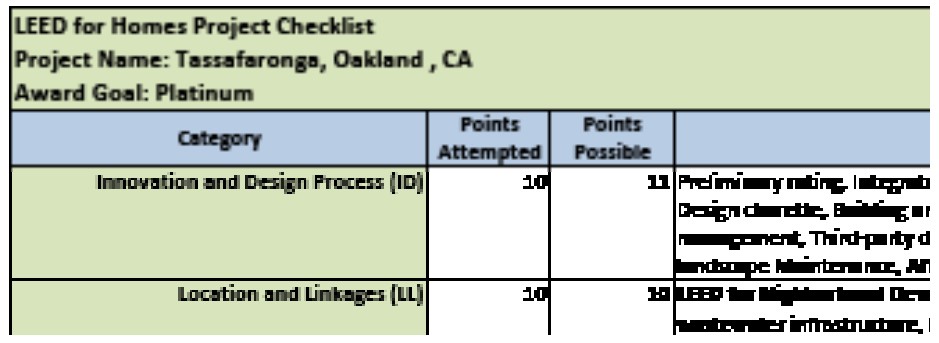

The LEED for Neighborhood Development Checklist for Tassafaronga Village, Oakland, California, USA. Image: David Baker + Partners Architects

Do you always pursue LEED? What are the benefits?

DB: We always suggest it. There are some marketing advantages, but I also think it’s a really great way to organize the team. It really is a broad-based, comprehensive standard.

DS: A building is an incredibly complicated thing, with millions of moving parts and hundreds of people involved. Keeping track of all the little decisions that you need to make, is hard. By bringing some accountability to the process, LEED helps you keep track of those things.

DB: There was some study, where they figured out that if you do random blower door tests, the quality of your insulation goes up substantially because they really don’t want to redo it. So the contractors end up saying, “You know, they’re going to do one of those goddamn blower tests, so take a little bit more time with it to get it right.”

DS: We’ve done projects that are LEED certifiable, where we did the checklist, and just didn’t do the certification process. It’s not a bad thing, it’s better than nothing, but it’s not a LEED certified building. It’s like saying, “I took the class, I just didn’t take the final.”

Is it typical of the client to pay for the registration?

DB: Somebody has to, and that can be a big sticking point. The registration fees are about $80 000. On a $43 million project, $80 000 is not a lot. But on smaller projects, there is a lot you can with $80 000 to improve the building. So a lot of nonprofits will ask, “Why should I pay for this certification when I can put a stone countertop in each unit for the cost of registration?”

Do you try to use innovative technologies in your projects?

DS: We work in a realm where we’re housing a lot of families, so there’s only so much innovation involved, because experimentation implies a certain level of failure and you don’t want to experiment with the poor, obviously. We want maybe 95 percent of the things we’re putting in to be as tried and true as possible. Nonprofits don’t have a lot of money and they want their operating costs to be super low. So if we design a super complicated system that has to be tuned every year or two, it won’t happen and it will stop working.

DB: The more complicated a system, the more things you have to fix. I’d rather just open a window in the corridor than have a high-tech fan system.

How often do you do value engineering? What do you fight to maintain?

DB: Constantly. We have our primitive strategies. Basically, we lard the roast. So you’ll have an outer ring of defenses, and then you’ll get stuff you care about more. It varies. We didn’t have that solar system in Tassafaronga Village, and it was big, $700 000 USD or $800 000 USD. Then we had the savings to pay for it, because the economic climate changed.

DS: Construction cost is all subjective. It’s not as absolute as you think and sometimes it surprises us. There was one mechanical system that we were thinking about using, that seemed a little bit nicer. It turned out that the nicer one, in this particular instance, from this particular subcontractor, was cheaper. So now our project has a nicer mechanical system in it, but the fact is, on another project, I would have been wrong.

DB: Sometimes people start with the idea Take All The Nice Stuff Out, which is anything nice that they can see, like nice windows. We try to spend more money on windows because that’s one of the ways you achieve higher sustainability. They do perform better, and it’s not as noisy. For a long time, we had to fight so hard to get anything beyond the worst imaginable technical performance on the windows, and we just got to the point where we had to say “Sorry, we just have good windows.”

DS: The contractor is always brought on early, usually in schematic design, or design development. It’s much more iterative: they’re doing budgets every two or three months. We are able to control the costs better that way than the traditional design, bid, build process.

DB: We’ve done away with the competitive bid process; we did that a few times, maybe in the ‘80s and it was always a disaster.

What were some of the design changes you made to the Tassafaronga Village Project?

DB: We struggled with the townhouses in particular because we wanted to do something that was modern but contextual, which is very difficult. There are not that many unit plans but they are pinwheeled. They are rotated and flipped.

There are only three or four unit plans in the whole townhouse scheme and three in the apartment building. It is common to try to minimize the number of different unit plans. First of all, you have code issues, it is an immense amount of work to get units to be efficient and code-compliant. Second, in terms of construction, these buildings need to have a certain amount of repetition or they get too expensive. So we did this Victorian idea that you can have the same unit with a different facade.

The question is, “How do you take a super cheap material and make it more interesting?” For example, we used HardiePlank siding, and we did a fancy detail with a very prosaic material, just a thin piece of sheet metal at the joint. You don’t want to join HardiePlank horizontally, so this allows you to use it more efficiently because you don’t have any long runs that give you problems with expansion and contraction.

On the pasta factory, [the entry screens] were going to be solar collectors, but the Oakland Housing Authority said, “We want them on the roof because then we can have more of them, and they will be less susceptible to vandalism.”

We came up with this idea of doing stormwater management. What triggered that was the LEED-ND goals, so we talked the city of Oakland into letting us bio-filter the street water, which was really hard to do. Stormwater management has become code now.

We also included traffic-calming features, and this is not a traffic-calmed area of Oakland. So originally people were just driving over the curbs where we had sidewalk extensions. We had to add bollards. Recently, some truckers decided that driving through this site is a shortcut. So all these gigantic rigs try to go through and get stuck. They put up “Trucks Not Allowed” signs, but they still come.

Have Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Integrated Project Design (IPD) strategies facilitated this process?

DB: Absolutely, contractors are doing it because it gives them a competitive advantage, and we like working with those contractors.

DS: We have a project in schematic design right now, where we’re going through a bunch of iterations on the exterior. We gave the contractor a 3D building model and they mapped the materials on it, did take-offs, sent us back color-coded PDFs with a table at the bottom of the sheet of square footages of each one. They’re able to say, “This material at this square footage in these locations on the building will cost this much,” which allows us to make direct comparisons. That’s real value engineering; that kind of analysis of the budget helps you figure out where you get the most bang for your buck.

DB: Right, they take the Revit models, use them with other contractors and put them into NavisWorks and figure out all the crashes. It’s really amazing because if you figure out all these discrepancies in your working drawings before you build it, it’s a lot easier to fix than out in the field, which is the old way.

Do you ever work with physical models?

DB: We typically build a small-scale site model, usually a presentation and community tool so people understand how it fits in. I don’t think physical models are a good way to work, because the labor-flexibility ratio is too high. Personally, I think—and this will sound weird—instead of building a beautiful professional, one-sixteenth-inch model, you should build a room full-scale. They’re both about the same cost, and a room is really interesting and useful.

What are the things that can go wrong? Do you have a good example?

DB: We always have problems, nothing is ever perfect. Sometimes I feel like Coyote in the Roadrunner cartoons.

DS: You can design a really fantastic building but if it isn’t maintained and the residents hate the management, then it doesn’t matter. There is a limit to how much great design can improve the quality of living. We are lucky that a lot of the nonprofits we work with are great. They are really good at managing buildings and making nice places for people to live.

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT