| Location | Wadi-Naam, Israel |

| Date | 2003 |

| Client | Bedouin community |

| Sponsoring Organization | Bustan |

| Design Team | Michal Vital and Yuval Amir |

| Structural Engineer | Ofer Cohen |

| Mechanical Engineer | Dror Zchori |

| Consultant | Kibutz Lotan Ecological Center |

| Construction | Volunteers |

| Major Funding | Private donations from the United States |

| Cost | $25,000 |

| Area | 753 sq. ft./70 sq. m |

The village of Wadi-Naam in Israel’s northern Negev Desert holds its annual festival during the week of Passover.

Here, during the spring celebration of 2003, several hundred volunteers descended upon the village to build a clinic that would serve as a powerful testament to the marriage of design and what its designers call “the public performance of civil disobedience.”

Home to some 4,000 Bedouins, Wadi-Naam is a no man’s land, one of many in the Negev. Sometimes called Israel’s “last frontier,” the Negev is a triangular stretch of desert bordered by Egypt on one side and Jordan on the other. Here squatter settlements of once-nomadic Bedouins and wealthy suburbanites compete over land rights and scarce resources. Israel is not the only country experiencing land conflicts between formal communities and unplanned settlements, but its politically charged history makes these conflicts all the more complex.

The group behind the clinic’s sudden appearance was Bustan, a partnership of Jewish and Arab eco-builders, architects, academics, and farmers. Since 1999 Bustan—”grove” in both Hebrew and Arabic—has been working to promote social change and environmental justice in Israel and Palestine, with a particular focus on the Bedouin villages of the Negev. According to the group’s founder and director, Devorah Bruos: “The Bedouin have become an underclass, unrecognized and therefore not connected to water, electricity, sanitation, or any other state infrastructure. [They are] denied permits for sewers, access roads, and municipal garbage-collection services.”

In the case of Wadi-Naam, she says, heavy pollution worsens its plight. The village is located less than 1.25 miles (2 km) from Israel’s largest toxic-waste incinerator, Ramat Hovav. During the 1980s an electric company built a power plant in the center of the village, but the village’s ”unrecognized” status meant residents could not benefit from its output. Many live in overcrowded shanties, and without adequate access to potable water, sanitation, or power, these conditions are detrimental to people’s health. “Incidents of asthma, bronchitis, skin cancer, miscarriages, and eye infection are substantially higher among Bedouin children than all other segments of the Israeli population,” says Bruos.

In early 2003 her group began circulating plans to build an environmentally sustainable medical facility in Wadi-Naam, where earlier efforts to install a clinic had faltered due to the village’s unrecognized status, despite a court order mandating its construction. Notified by word-of-mouth, several hundred Israeli and foreign volunteers traveled to the village during Passover to build a medical clinic alongside residents in less than six days. “The Medwed project was undertaken with the understanding that it is an unauthorized structure in an unrecognized place that may be bulldozed without any advance notice,” Bruos explains.

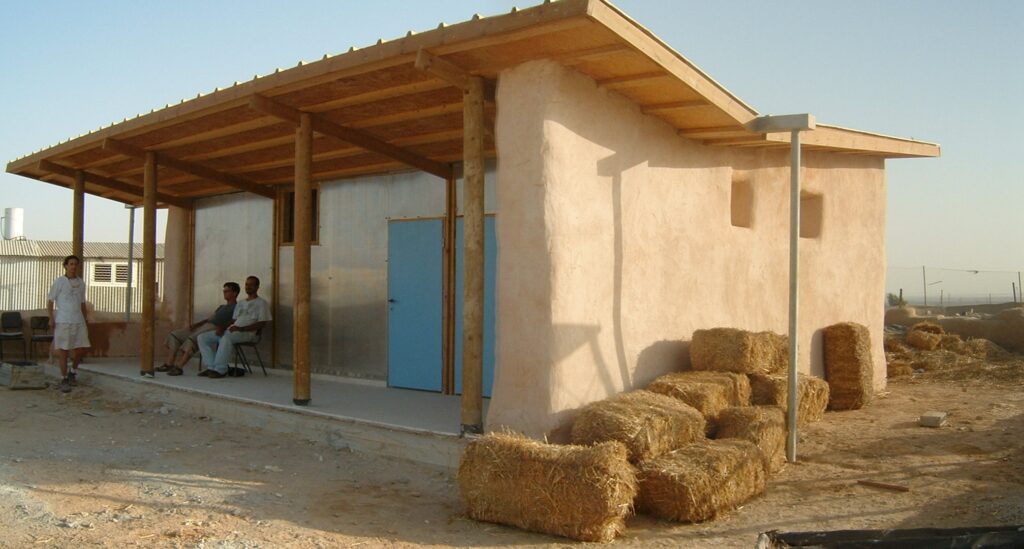

The unusual circumstances of construction led to a number of design challenges. The entire clinic had to be as low-tech as possible while providing proper medical care. It had to function outside the official system and be built using inexpensive natural resources and unskilled volunteer labor. And it had to be erected quickly. Given these constraints, architects Michal Vital and Yuval Amir turned to straw-and-adobe construction, which has a long history in Bedouin culture. (For more about hay-bale construction, see “Straw Bale Houses.”)

The clinic’s butterfly roof recalls the traditional Bedouin tent, and three of its exterior walls are made from mud-covered straw bales. The fourth wall is made from two layers of polycarbonate sheeting with vegetation grown in between. The clinic is divided into two parts, dry and wet areas, separated by an adobe brick wall. Inside the clinic a solar-powered refrigerator holds medical supplies. The team sited the building according to area wind patterns to allow for natural ventilation.

The clinic is situated within a shaded garden and enclosed by a perimeter fence made from adobe-covered tires. A rainwater collection system irrigates fruit trees and a medical herb garden. Outside there is also a traditional mud-brick oven, or taboun, designed and built by the village women. On busy days the garden doubles as a waiting area for mothers and children.

The result is a self-sustaining shaded structure that finds dignity in simplicity. For its originators, however, the complexity and politics of the project make it all the more meaningful. “This clinic is not just about medical rights for the citizens of Wadi-Naam,” says Brous. “It is about health security for all the Bedouin citizens in our shared homeland.”

“Pass the incinerator on Rt. 40 and 2 km down the road make a right at the sign reading Electric Company. That is the village entrance. Follow the two smoke stacks and the high-voltage pylons up the road and swerve left over the hill. There you will find us.”

Message posted to guide volunteers to the Medwed Clinic building site

Volunteers set tires in concrete to form a wall around the clinic. The tires are filled with sand to ensure stability. ©Alon Hertz

READ OR LEAVE A COMMENT